- Home Page

- Kiting Knots

- Knot Strength

Knot Strength

Test Results for Dacron Lines

You've probably heard it somewhere, while out kite flying—knot strength is a factor in the breaking strain of a kite line! Put simply, any piece of line will snap easier if it has a knot in it.

Line-mend with the Triple Granny!

Line-mend with the Triple Granny!I have set out to put some numbers on this and draw some conclusions.

The hope is that these results, and particularly the Overall Conclusions, will be of interest to nearly all kite fliers who use 100-pound line or less. I'm sure there is at least some relevance for people who use heavier grades of line too.

Now, there are all kinds of knots out there, for all kinds of purposes. But I'm going to just look at those that you are most likely to use (or find!) between your kite's anchor point on the ground and the flying line's attachment point to the bridle. If any of those let go, you know what happens!

Furthermore, I mainly fly single-liners, so the tests have been done on Dacron only. That happens to be by far the most popular type of flying line for most single liners.

Dacron is a trade name for a polyester product.

On this site, there's more kite-making info than you can poke a stick at. :-)

Want to know the most convenient way of using it all?

The Big MBK E-book Bundle is a collection of downloads—printable PDF files which provide step-by-step instructions for many kites large and small.

That's every kite in every MBK series.

Overall Conclusions

I'm guessing you might not want to wade through all the data before getting to the results. :-)

In a nutshell:

- Sheer age seems to waste away a large proportion of the strength of braided Dacron line. Old hands would be well aware of this, but newbies beware.

- There are several fairly easy line-mending knots that will achieve a breaking strain of between 60% and 75% of the line's unknotted strength. That's not its shop rating, but its actual strength on the day!

- The Blood knot takes patience to master, but even with a simplified version I achieved between 80% and 95% results over the three very different weights of line tested. That is, 20-, 50-, and 100-pound shop ratings.

- The very popular Lark's Head attachment method is quite strong, even when formed with a Simple (overhand) Loop knot. One result, using the Figure Eight Loop, even came close to 100% of unknotted strength!

Other interesting points:

Sometimes the results were more scattered than expected. I suspect this was a result of real-world imperfect knot tying! For example, there could be some twist in the line before knotting. A less tight part of the knot might suddenly come tight causing friction and loss of strength and so on. Frays and wear were NOT a factor, since unused line was being tested.

There was some evidence that rectangular-section line can be much stronger than round-section line—if tied well! As the wide side wraps around sharp corners, there would be less strain at the outside of the turn, compared with round-section line of the same weight. Logical enough, do you agree?

This whole exercise reflected imperfect knot-tying and realistically old line. Would the results from perfect knots and perfect spanking-new line be as relevant? Perhaps not, so I'm seeing this as a positive. :-)

No Knot

First up, we need to know the line strengths with no knots in at all. So here's what happened when the lines were carefully anchored at each end, before being pulled to breaking point. For the 20-pound line, I made sure the line had snapped some distance from each anchor point. In other words, my anchoring method had not weakened the line in any measurable way.

Unfortunately, this was harder to achieve with the 50-pound line. Six times in a row it snapped at either top or bottom, with quite a bit of variation in results! After the 200-pound anchor line was sleeved with sticky tape, I seemed to get more consistent results, hence the three of them are recorded below. Going by the 20-pound line experience, the 50-pound figures should be quite close to the true breaking strain of the line, despite all letting go at the bottom attachment point of the test rig.

For the 100-pound line tests, the 200-pound anchor points were doubled up to prevent the test lines breaking at the anchor points.

So these "no knot" numbers were a touch low. However, they were close enough to allow useful comparisons of all the knots tested.

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

20

14, 14, 12

13.3

50

44, 42, 42

42.7

100

62, 60, 62

61.3

Line-Mending Methods

Some of those fancy fishing knots are almost impossible to tie into light Dacron or nylon, I've found. Others are quite doable, even with 20-pound line.

Who hasn't snapped a line, ever? I thought so. To tell the truth, it's only happened to me once with a standard braided Dacron flying line. Come to think of it, it was with some of this under-strength 20-pound line. :-|

The same cannot be said when flying small kites on thread, however. ;-) Big thermal gusts would sometimes come through and part the line. Anyhow...

Multi-Strand Double Knot

A convenient way to reconnect a broken line is to use the Multi-Strand Double knot. Ugly, but it's easy to remember and certainly holds tight! It's just an overhand knot with the lines passed through twice instead of once. If you think about it for a moment, you will realize that this knot looks exactly the same as a Double Loop knot where the loop has been snipped in two. Hence the Double Loop results further down are just a copy of this table.

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

6, 8, 7

7.0

53

50

32, 29, 28

29.7

69

100

47, 42, 45

44.7

73

Fisherman's Knot

Although the tightened knot looks complex, the Fisherman's knot is actually very easy to tie. Basically, each end is attached to the other with a simple overhand knot, before the two knots slip together when the lines are pulled. As you can see, this does weaken the line more than some other knots. By the way, I read somewhere that fishermen don't actually use this knot. :-)

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

8, 9, 8

8.3

63

50

30, 30, 27

29.0

68

100

41, 36, 44

46.7

76

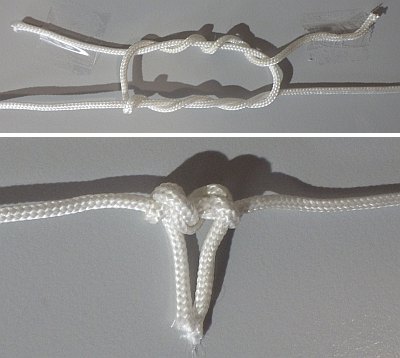

Triple Granny Knot

The classic Granny itself just slips through, but if you wind around three times in both overhand knots instead of just once, bingo! The Triple Granny knot holds and is significantly stronger than the Multi-Strand Double knot.

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

10, 9, 9

9.3

70

50

32, 29, 32

31.0

73

100

48, 46, 46

46.7

76

Blood Knot

This rather long knot looks a bit complex at first but is actually quite simple to remember. Since polyester is not as slippery as wet fishing line or spectra, I used just three turns on each side. Great results were obtained!

The Blood knot is quite fiddly to tie with light line, but it comes with a bit of practice. If you do it correctly, you are rewarded with an impressively secure connection of the two lines. Just look at those figures below:

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

13, 14, 11

12.7

95

50

38, 38, 31

35.7

84

100

46, 52, 56

51.3

84

Now, there is one knot that can outperform even the Blood knot, called the Bimini Twist. I consider it somewhat "over the top" for us casual kite fliers though. So I'm leaving it as an exercise for the reader to look up and try the Bimini wonder-knot. :-)

But wait, there's more. ;-) If you really, really need a perfect connection in braided line, there is a way: Unpick both ends with an appropriate tool and splice them together. Bingo, it's 100% secure if it's done like a pro! Personally, I can't be bothered. Also, this approach is not practical with line weights less than about 200 pounds because the individual strands in the braid are so small. You'd need a microscope!

Conclusions: Line-Mending Knots

If you really need a very strong connection, the simplified (three turns-a-side) Blood knot is a great choice as long as the knot is consistently tied well so it looks very even and symmetrical. Mine could have been done better, hence the considerable scatter in those results for the 100-pound line. Maybe it's easier with round-section line.

Personally, the very consistent and dead-easy Triple Granny will be my choice from now on. Unless someone else has come up with it independently, I'm claiming the invention of this knot. :-)

Mid-Line Scenarios

Let's look at knots you might use along the line somewhere. Some of these have been known to just appear mysteriously, history unknown!

Simple Knot

Often referred to as the overhand knot. Occasionally it happens by accident, near the free end of a line. You're handling the line and notice a Simple knot, pulled extremely tight because it's had a ton of flying over the last few months! Bummer. So just how much has it weakened the line?

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

7, 9, 8

7.0

60

50

25, 27, 23

25.0

59

100

46, 47, 49

47.3

77

Figure Eight Knot

It's also possible for the Figure Eight knot to appear by accident near the end of a flying line. This knot is useful for preventing pull-through in various other knots, but might also be used deliberately in a flying line as a stop. For example, it can stop a line-climbing device from going any higher.

Amazingly, for my 20-pound line, the three pull-test results were the same as for the simple overhand knot—and in the same order! I was expecting this knot to be slightly stronger, but apparently it's not.

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

7, 9, 8

8

60

50

26, 23, 22

23.7

55

100

42, 47, 46

45.0

73

Simple Loop Knot

The Simple Loop knot is also known as the Overhand Loop knot. This is a handy knot that most of us have probably put into a kite line for one reason or another—perhaps to dangle something from the line or perhaps to hang a smart phone or camera cradle from the flying line.

Sad to say, this knot is sometimes known to appear by accident, like the Simple or Figure Eight knots! Note that it IS possible for this knot to simply pull out when tied mid-line. I saw it happen on my test rig. I redid the test, of course.

The Simple Loop is not the best choice for putting a loop mid-way along a line. Here are the testing results:

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

7, 7, 5

6.3

48

50

23, 23, 26

24.0

56

100

38, 36, 40

38.0

62

Figure Eight Loop Knot

Despite looking more sophisticated, the Figure Eight Loop knot didn't perform much differently to the Simple Loop on old kite line. Apparently this knot is often used by sailors to put in a mid-line loop. Perhaps they shouldn't:

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

7, 8, 8

7.7

58

50

21, 24, 22

22.3

52

100

36, 44, 44

41.3

67

Double Loop Knot

This more robust version of the Simple Loop is what I use to attach a suspension line to the flying line for kite aerial photography (KAP). When tying it, the loop is passed through twice instead of once. That's easy to remember, and it will never pull through.

I also put tiny Double Loops into my lines to indicate length in 30 meter (100 feet) intervals. This might shock some serious kite-fliers who are justified in using well-looked-after unknotted line when putting up their large inflatables in fresh winds! My Skewer and Dowel Series kites are rarely flown above 30 kph.

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

6, 8, 7

7.0

53

50

32, 29, 28

29.7

69

100

47, 42, 45

44.7

73

Butterfly Loop Knot

The Butterfly Loop is known by a variety of names, such as the Alpine Butterfly, Lineman's Loop, and Lineman's Rider. This was a late addition, suggested by kite designer Bazzer Poulter.

Can you tell the origins of this knot were in mountain climbing? But, as a kite flier, I'll be hanging onto to this one (no pun intended har har) since the results are generally superior to the other knots. The 50-pound line results were comparable to the Double Loop knot, but for the other weights the difference was very distinct:

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

10, 10, 9

9.7

73

50

30, 28, 25

27.7

65

100

51, 51, 52

51.3

84

Conclusions: Mid-Line Knots

For suspending my KAP rig, I've been quite happy with the Double Loop knot, but will consider using the Butterfly from now on! Or perhaps it will be used on a new line one day. I would still recommend the Double Loop for most fliers, since it is dead easy to remember and tie. The Butterfly offers better strength if you decide you want or need it. Of course, there are fancier solutions (devices) for hanging things off your line that don't involve putting any knot in the flying line itself.

Kite-End Knots

That is, the attachment of the flying line to the bridle.

The Lark's Head can be formed with any Loop knot, so I've shown strength results for three handy variations here. The great thing about this attachment method is how easy it is to remove from the bridle. Actually, 20-pound line can be a bit fiddly, but it gets vastly easier in the heavier sizes.

One important note: These results are applicable when the flying line is Lark's Headed to a heavier line in the bridle. I have had a situation in the past where it was the bridle line that broke, just behind the terminating knot. The bridle line and the flying line were both 20-pound Dacron. I promptly replaced the short bridle line with 50-pound Dacron!

Lark's Head

(from Simple Loop knot)

A simple overhand loop is quick and easy to tie, in order to form the incredibly useful Lark's Head. What's more, it doesn't seem significantly weaker than the other knots tested, at least for the 20- and 50-pound lines.

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

10, 10, 11

10.3

78

50

30, 28, 31

29.7

69

100

48, 46, 48

47.3

77

Lark's Head

(from Double Loop knot)

A double overhand loop is my favorite base for making a Lark's Head. It's just like the Simple Loop except you pass the loop through once more before pulling tight. I used it for my largest kites, assuming it would have significantly more strength. But as you can see from the numbers, the Double Loop is quite similar to the Simple Loop when forming a Lark's Head.

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

10, 10, 10

10.0

75

50

32, 24, 26

27.3

64

100

49, 50, 48

49.0

80

Lark's Head

(from Figure Eight Loop knot)

For some reason, I just never got around to using the Lark's Head from a Figure Eight Loop knot. It's a good knot, with the first 100-pound pull-test returning an intriguingly strong result:

Rated Strength

(pounds)

Measured Strength

(pounds, for three tests)

Average

(pounds)

Percentage of

Unknotted Strength

20

8, 9, 12

9.7

73

50

29, 29, 32

30.0

70

100

60, 53, 46

53.0

86

Conclusions: Kite-End Knots

The knots tested all gave strong results, so there's nothing wrong with using the easiest one: the Lark's Head based on the Simple Loop knot. But perhaps the Figure Eight-based knot has the edge with heavier lines or perhaps all rectangular-section lines.

Knot Strength Testing Method

I finally settled on a simple pull-down method, after much consideration of how I might actually get the results. One end of the test rig was secured to a solid beam above head height. The other end of the test rig was secured to a short wooden bar, with room for a hand hold on either side:

Apparatus used for tests

Apparatus used for testsBy standing on a set of bathroom scales and pulling down on the bar, I could note the weight reading just prior to the line failure. My weight (including the short wooden bar) less the reading at failure gave the breaking strain. That was not super accurate, but the average of three readings told the story well enough to be useful.

To mount the length of line being tested, I used 200-pound Dacron for an anchor line over the high beam, and the same for a short line from the wooden bar at the other end. The line to be tested was triple wrapped behind a Figure Eight knot near the free end of each 200-pound line, before being secured with several Half-Hitches for easy removal.

Line weakening for the "no knot" scenario was kept to a reasonable minimum, since the surface of the 200-pound line was of large radius compared to the test lines secured around it. The test lines never broke at the Half Hitches, since there was very little curvature of the highly stressed portion of the line which ran through the hitches.

Although the "no knot" tests broke the test lines at one end or the other, it was deemed good enough for getting useful test results. After all, the main idea of the exercise was comparison rather than absolute accuracy.

During the tests, I ended up using only one or two wraps and two Half-Hitches at each end to secure the test line. In this way, it proved much easier to remove the remnants after each test, and there were no breaks at either anchor point. An exception was the 100-pound line tests! For these, I had to double the 200 pound Dacron to prevent breakages of the test line at the anchor points. The doubling made for an even larger effective radius for anchoring the thicker 100-pound line.

I had originally meant to use the Fisherman's Clinch knot to secure the length of line being tested, but it proved very difficult to remove after each test!

Old but Unused Line Surprise!

I was shocked when I completed the "no knot" tests for my 20-pound line. Had I been sold 10-pound line by mistake? It looked a bit like it, with all the breaking-strain numbers being 14 pounds or below! But I guess that's a lesson in itself; old line, even if unused, is not as strong as new line. So there you go. And it was a similar story with the 50-pound and 100-pound lines!

And no, the reels hadn't been sitting in the sun accumulating UV damage either. They were just there on a shelf in a shed with a small sky-light but no windows, going through changes in temperature and humidity for quite a few years.

The Numbers

Indicated weights on the mechanical scales were read to about +/- 1/4 pound. It was either near a two-pound division or somewhere in between! Finer estimations were not possible under the circumstances. Nor would they make any sense given the amount of variation in the results from test to test.

Why pounds? The greater number of divisions meant slightly better precision compared to reading off the kilograms scale! Besides: 1) pounds are very widely used for kite-line weights even in countries that are officially on the metric system and 2) the main thing of interest to us kite fliers is the percentages, wouldn't you agree? :-)

The averages are quoted to one decimal point. However, the full-precision figure was used to calculate the percentage of the "no knot" result. Percentages were then rounded to a whole number. In retrospect, it was probably pointless to use full precision anywhere, given the limited precision of the whole setup!

Other Notes

There's a quirk with my tests that should be mentioned. Although three different weights of line were used, they each came from a different source and also varied significantly in age. On top of that, the 50-pound line had relatively few strands in the braid.

Ideally, doing the tests with brand-new braided round-section line (from the same manufacturer!) for all three weights would give more insight into how line weight alone can affect knot-strength performance. Perhaps the larger number of individual fibers in the heavier weight material would improve knot strength.

But despite that quirk, I'll bet the tests done will be of much interest to kite fliers who use these lighter grades of line. There was certainly a surprise or two in there for me.

As mentioned earlier, there's more kite making on this site than you can poke a stick at. :-)

Want to know the most convenient way of using it all?

The Big MBK E-book Bundle is a collection of downloads—printable PDF files which provide step-by-step instructions for many kites large and small.

That's every kite in every MBK series.